Sunset V - Okavango Delta

You know when on Boxing Day your old man would be clicking it by 8:00am trying to load up the family Commodore for the annual pilgrimage down the south coast, and your sister would bring forth her newly delivered bike with the flashy handlebar tassels meaning something had to be removed from the car because we all packed too much…well, this morning was like that but in a foreign country, amplified by 15, and requiring the deconstruction of an overland tourer not a Holden Commodore.

Waking early and juggling what should have been a more honourable hangover, we had a quick breakfast then laid out all the essentials onto a clean tarpaulin for the Tetris style 3 dimensional jigsaw puzzle before us. Delta Rain delivered two specialist vehicles substantially smaller than our own Wilderbus for the journey to the Delta that both needed packing. Tents and beds of course were a must as were chairs and food, but every other luxury would remain with Mr B at Maun while we roughed it for a few days.

The group split into two for the 90 minute drive north-west and despite the opened sides of the vehicle, the brilliant morning sun warmed us all while endless conversations shortened the journey even more. At Ngamiland East we left the bitumen and flicked the free wheeling hubs over to 4WD for the winding road heading deeper into the delta. Reality started to hit as both the terrain and vegetation visibly shifted in only a matter of kilometres.

The Okavango Delta is formed by the Okavango River as it reaches a tectonic trough at an elevation of 1,000m above sea level in the central part of the endorheic basin of the Kalahari Desert. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of only a few interior delta systems not flowing to a sea or ocean but largely remaining a wetland system with the water ultimately evaporated or transpired. Each year about 11 cubic kilometres of water spreads over the 15,000 square kilometre area.

Produced by seasonal flooding of the river after draining summer rainfall (Jan - Feb) from the Angola highlands to the north-west, surge flows can reach 1,200km in a single month. The waters then spread over the entirety of the delta for the next four months (March–June) before rapidly evaporating due to the high temperatures of the region. This all results in three cycles of rising and falling water levels where the delta swells to three times its permanent size attracting animals from kilometres around and creating one of Africa’s greatest concentrations of wildlife. The delta is extremely flat with a variation in height less than 2m across its expanse with the water dropping only about 60m from Mohembo to Maun.

Driving through swelling creeks and wetlands teeming with bird-life, it all got very exciting very quickly and before long we’d reached our drop off point. Deep within the outskirts of the delta we met our “polers” and their mokoros that would take over the transportation from here.

A mokoro is a type of dugout canoe commonly used in the Okavango and on the Chobe River in Botswana. It is propelled through the shallow waters by a poler standing at the stern and pushing against the riverbed with a pole, and traditionally made by hollowing out the trunk of a large straight tree. Modern mokoros however are increasingly made of fibreglass in the aim of preserving such large trees but the boats still remain a practical means of transport for locals to navigate the waterways. They are however very vulnerable to attack by hippopotami which can overturn them with ease. Hippos are reputed to have developed this behaviour because mokoros have also been used for hunting - that most definitely wasn’t in the brochure!

We were all briefed on the requirements and dangers of mokoro travel and outfitted with life jackets, as if they would ward off a hippo, before boarding our craft for the approximate 1hr journey upstream to our camp site.

Straight away this was very cool. Like really super cool to be at river level in the middle of Botswana silently gliding through shallow waters and eye-height reeds with only the sound of ripples hitting the bow and elephants swatting mud from the roots of grass they’d just removed. This WAS in the brochure and exactly as foreshadowed. Balance was of initial concern as the mokoros are pretty unstable, but once Fatpap composed the movement of his 120kg frame our poler found things a little more manageable. Working against what little current there was, and with absolutely not a breath of wind, we continued north passing dozens of elephants closer to shore foraging for their 300kgs of required daily grass intake.

The journey was surreal and truly a once in a lifetime experience. That’s a superlative we don’t throw around very often, if at all, but this was one for the books and so vastly different to anything else we have done. Our flotilla breeched the shoreline hidden in an unseen channel to alight and find a semi-permanent camp awaiting our arrival. The camp was run by a tribe of locals who lived “just around the corner” now making their living in the tourism industry. The specialty trucks had been and gone leaving all our equipment neatly piled as had it been earlier that morning, so we pitched our tents, had a tour of the long-drop shitter and admired the view as lunch was upon us. Huddled under a canvas pavilion we ate while 2 dozen elephants did the same only a 100m away.

With time to relax, the first since leaving Johannesburg, we had literally been on the go the whole way maintaining a tight schedule over great distances, many of us just sat and watched the “elephant channel” with barely a word spoken between us. And on that channel not a single man-made object could be found. No planes soaring above nor din of traffic in the distance. The sky was blue, the grass was green and nature the only sound audible. This was Africa at its finest, perhaps not what most would expect of the continent, but to us 15 explorative souls exactly why we came to this magnificent land. It was also of course an appropriate time for the much anticipated, and highly coveted traditional gratuitous bun shot. You’re all more than welcome.

Late afternoon we had a walking safari planned and again split into two groups and explained the machinations of safaris on foot. Single file trekking based on shortest to tallest and obviously low voices or preferably no talking at all. To gain another’s attention, one could whistle briefly and point in the direction of a sighted varmint. It was really very exciting.

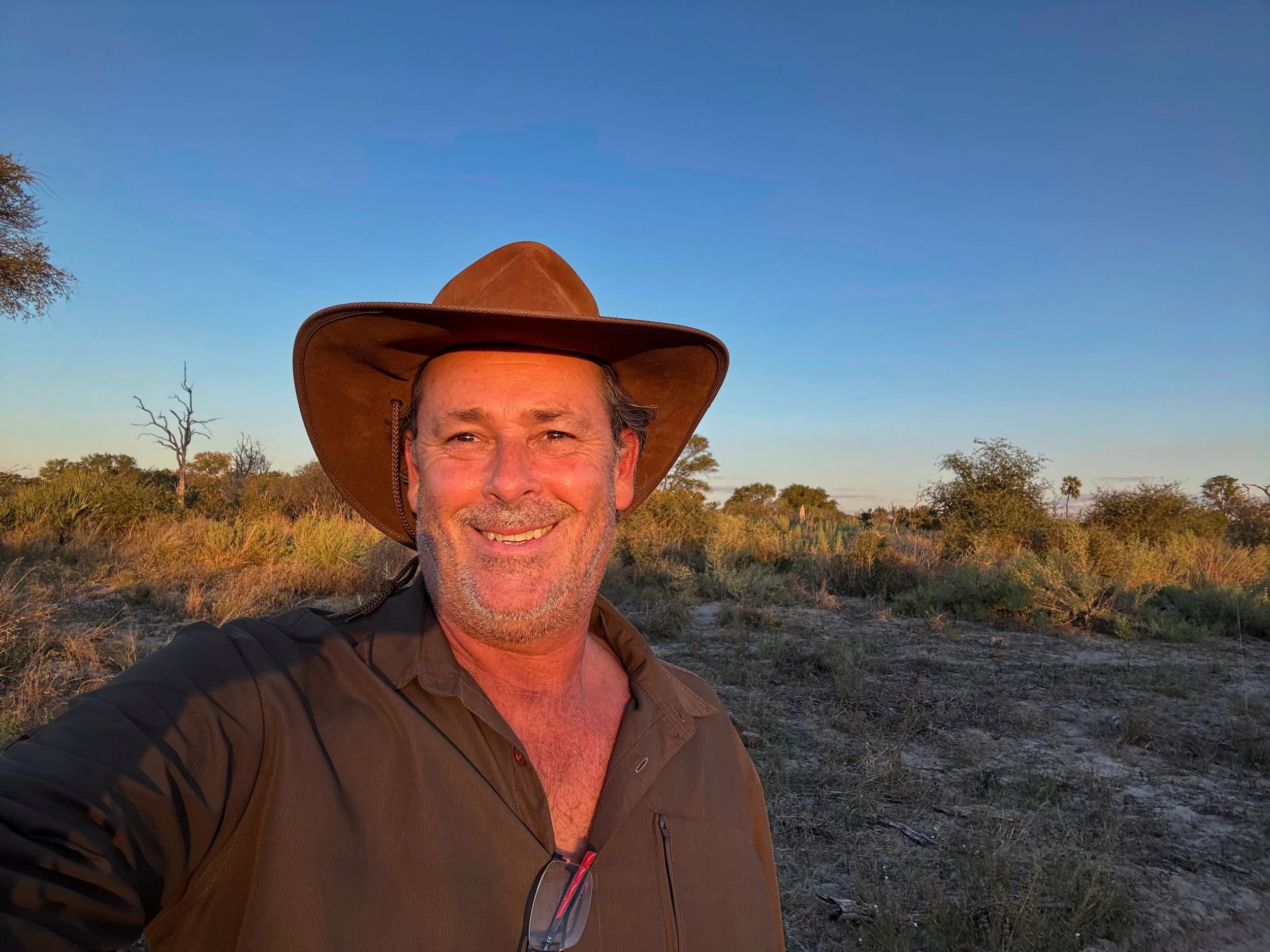

The delta is primarily known for its elephant and hippopotamus populations however all number of animals thrive in the area. We spotted impalas and warthogs together with dozens of different bird species, while hyena and lion tracks were pointed out among the scores of others on the sandy floor. The guides were expectantly excellent not only seeing things way before any of us did, but their knowledge of the land was incredible making the entire experience both informative and enjoyable. Our fifth African sunset soon arrived bringing with it the unmistakable golden hour tones honestly not ever seen before. Due to a combination of atmospheric conditions and geographical factors, the presence of dust and pollution in the air create a unique environment for light refraction and scattering resulting in the spectacular hues we saw every day. But to most, it just looked so pretty.

Nola had a team of helpers tonight who between them conjured yet again the most wholesome and delicious dinner imaginable. We enjoyed the food under our camp pavilion conscious of the hippos now making their way to land after a day of wallowing in the shallows. It was a brilliant first day on the delta with many exhausted both physically and emotionally so it was either to bed or the open fire chatting with our new desert guardians for most, but not before being escorted to the shitter ahead of any tent lockdown occurring.